Sylow theorems

In mathematics, specifically in the field of finite group theory, the Sylow theorems are a collection of theorems named after the Norwegian mathematician Ludwig Sylow (1872) that give detailed information about the number of subgroups of fixed order that a given finite group contains. The Sylow theorems form a fundamental part of finite group theory and have very important applications in the classification of finite simple groups.

For a prime number p, a Sylow p-subgroup (sometimes p-Sylow subgroup) of a group G is a maximal p-subgroup of G, i.e., a subgroup of G which is a p-group (so that the order of any group element is a power of p), and which is not a proper subgroup of any other p-subgroup of G. The set of all Sylow p-subgroups for a given prime p is sometimes written Sylp(G).

The Sylow theorems assert a partial converse to Lagrange's theorem that for any finite group G the order (number of elements) of every subgroup of G divides the order of G. For any prime factor p of the order of a finite group G, there exists a Sylow p-subgroup of G. The order of a Sylow p-subgroup of a finite group G is pn, where n is the multiplicity of p in the order of G, and any subgroup of order pn is a Sylow p-subgroup of G. The Sylow p-subgroups of a group (for fixed prime p) are conjugate to each other. The number of Sylow p-subgroups of a group for fixed prime p is congruent to 1 mod p.

Contents |

Sylow theorems

Collections of subgroups which are each maximal in one sense or another are common in group theory. The surprising result here is that in the case of Sylp(G), all members are actually isomorphic to each other and have the largest possible order: if |G| = pnm with  where p does not divide m, then any Sylow p-subgroup P has order |P| = pn. That is, P is a p-group and gcd(|G:P|, p) = 1. These properties can be exploited to further analyze the structure of G.

where p does not divide m, then any Sylow p-subgroup P has order |P| = pn. That is, P is a p-group and gcd(|G:P|, p) = 1. These properties can be exploited to further analyze the structure of G.

The following theorems were first proposed and proven by Ludwig Sylow in 1872, and published in Mathematische Annalen.

Theorem 1: For any prime factor p with multiplicity n of the order of a finite group G, there exists a Sylow p-subgroup of G, of order pn.

The following weaker version of theorem 1 was first proved by Cauchy.

Corollary: Given a finite group G and a prime number p dividing the order of G, then there exists an element of order p in G .

Theorem 2: Given a finite group G and a prime number p, all Sylow p-subgroups of G are conjugate to each other, i.e. if H and K are Sylow p-subgroups of G, then there exists an element g in G with g−1Hg = K.

Theorem 3: Let p be a prime factor with multiplicity n of the order of a finite group G, so that the order of G can be written as pn · m, where n > 0 and p does not divide m. Let np be the number of Sylow p-subgroups of G. Then the following hold:

- np divides m, which is the index of the Sylow p-subgroup in G.

- np ≡ 1 mod p.

- np = |G : NG(P)|, where P is any Sylow p-subgroup of G and NG denotes the normalizer.

Consequences

The Sylow theorems imply that for a prime number p every Sylow p-subgroup is of the same order, pn. Conversely, if a subgroup has order pn, then it is a Sylow p-subgroup, and so is isomorphic to every other Sylow p-subgroup. Due to the maximality condition, if H is any p-subgroup of G, then H is a subgroup of a p-subgroup of order pn.

A very important consequence of Theorem 2 is that the condition np = 1 is equivalent to saying that the Sylow p-subgroup of G is a normal subgroup (there are groups which have normal subgroups but no normal Sylow subgroups, such as S4).

Sylow theorems for infinite groups

There is an analogue of the Sylow theorems for infinite groups. We define a Sylow p-subgroup in an infinite group to be a p-subgroup (that is, every element in it has p-power order) which is maximal for inclusion among all p-subgroups in the group. Such subgroups exist by Zorn's lemma.

Theorem: If K is a Sylow p-subgroup of G, and np = |Cl(K)| is finite, then every Sylow p-subgroup is conjugate to K, and np ≡ 1 mod p, where Cl(K) denotes the conjugacy class of K.

Examples

A simple illustration of Sylow subgroups and the Sylow theorems are the dihedral group of the n-gon,  For n odd,

For n odd,  is the highest power of 2 dividing the order, and thus subgroups of order 2 are Sylow subgroups. These are the groups generated by a reflection, of which there are n, and they are all conjugate under rotations; geometrically the axes of symmetry pass through a vertex and a side. By contrast, if n is even, then 4 divides the order of the group, and these are no longer Sylow subgroups, and in fact they fall into two conjugacy classes, geometrically according to whether they pass through two vertices or two faces. These are related by an outer automorphism, which can be represented by rotation through

is the highest power of 2 dividing the order, and thus subgroups of order 2 are Sylow subgroups. These are the groups generated by a reflection, of which there are n, and they are all conjugate under rotations; geometrically the axes of symmetry pass through a vertex and a side. By contrast, if n is even, then 4 divides the order of the group, and these are no longer Sylow subgroups, and in fact they fall into two conjugacy classes, geometrically according to whether they pass through two vertices or two faces. These are related by an outer automorphism, which can be represented by rotation through  half the minimal rotation in the dihedral group.

half the minimal rotation in the dihedral group.

Example applications

Cyclic group orders

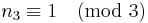

Some numbers n are such that every group of order n is cyclic. One can show that n = 15 is such a number using the Sylow theorems: Let G be a group of order 15 = 3 · 5 and n3 be the number of Sylow 3-subgroups. Then  and

and  . The only value satisfying these constraints is 1; therefore, there is only one subgroup of order 3, and it must be normal (since it has no distinct conjugates). Similarly, n5 must divide 3, and n5 must equal 1 (mod 5); thus it must also have a single normal subgroup of order 5. Since 3 and 5 are coprime, the intersection of these two subgroups is trivial, and so G must be the internal direct product of groups of order 3 and 5, that is the cyclic group of order 15. Thus, there is only one group of order 15 (up to isomorphism).

. The only value satisfying these constraints is 1; therefore, there is only one subgroup of order 3, and it must be normal (since it has no distinct conjugates). Similarly, n5 must divide 3, and n5 must equal 1 (mod 5); thus it must also have a single normal subgroup of order 5. Since 3 and 5 are coprime, the intersection of these two subgroups is trivial, and so G must be the internal direct product of groups of order 3 and 5, that is the cyclic group of order 15. Thus, there is only one group of order 15 (up to isomorphism).

Small groups are not simple

A more complex example involves the order of the smallest simple group which is not cyclic. Burnside's paqb theorem states that if the order of a group is the product of two prime powers, then it is solvable, and so the group is not simple, or is of prime order and is cyclic. This rules out every group up to order 30 (= 2 · 3 · 5).

If G is simple, and |G| = 30, then n3 must divide 10 ( = 2 · 5), and n3 must equal 1 (mod 3). Therefore n3 = 10, since neither 4 nor 7 divides 10, and if n3 = 1 then, as above, G would have a normal subgroup of order 3, and could not be simple. G then has 10 distinct cyclic subgroups of order 3, each of which has 2 elements of order 3 (plus the identity). This means G has at least 20 distinct elements of order 3. As well, n5 = 6, since n5 must divide 6 ( = 2 · 3), and n5 must equal 1 (mod 5). So G also has 24 distinct elements of order 5. But the order of G is only 30, so a simple group of order 30 cannot exist.

Next, suppose |G| = 42 = 2 · 3 · 7. Here n7 must divide 6 ( = 2 · 3) and n7 must equal 1 (mod 7), so n7 = 1. So, as before, G can not be simple.

On the other hand for |G| = 60 = 22 · 3 · 5, then n3 = 10 and n5 = 6 is perfectly possible. And in fact, the smallest simple non-cyclic group is A5, the alternating group over 5 elements. It has order 60, and has 24 cyclic permutations of order 5, and 20 of order 3.

Fusion results

Frattini's argument shows that a Sylow subgroup of a normal subgroup provides a factorization of a finite group. A slight generalization known as Burnside's fusion theorem states that if G is a finite group with Sylow p-subgroup P and two subsets A and B normalized by P, then A and B are G-conjugate if and only if they are NG(P)-conjugate. The proof is a simple application of Sylow's theorem: If B=Ag, then the normalizer of B contains not only P but also Pg (since Pg is contained in the normalizer of Ag). By Sylow's theorem P and Pg are conjugate not only in G, but in the normalizer of B. Hence gh−1 normalizes P for some h that normalizes B, and then Agh−1 = Bh−1 = B, so that A and B are NG(P)-conjugate. Burnside's fusion theorem can be used to give a more power factorization called a semidirect product: if G is a finite group whose Sylow p-subgroup P is contained in the center of its normalizer, then G has a normal subgroup K of order coprime to P, G = PK and P∩K = 1, that is, G is p-nilpotent.

Less trivial applications of the Sylow theorems include the focal subgroup theorem, which studies the control a Sylow p-subgroup of the derived subgroup has on the structure of the entire group. This control is exploited at several stages of the classification of finite simple groups, and for instance defines the case divisions used in the Alperin–Brauer–Gorenstein theorem classifying finite simple groups whose Sylow 2-subgroup is a quasi-dihedral group. These rely on J. L. Alperin's strengthening of the conjugacy portion of Sylow's theorem to control what sorts of elements are used in the conjugation.

Proof of the Sylow theorems

The Sylow theorems have been proved in a number of ways, and the history of the proofs themselves are the subject of many papers including (Waterhouse 1980), (Scharlau 1988), (Casadio & Zappa 1990), (Gow 1994), and to some extent (Meo 2004).

One proof of the Sylow theorems exploit the notion of group action in various creative ways. The group G acts on itself or on the set of its p-subgroups in various ways, and each such action can be exploited to prove one of the Sylow theorems. The following proofs are based on combinatorial arguments of (Wielandt 1959). In the following, we use a | b as notation for "a divides b" and a  b for the negation of this statement.

b for the negation of this statement.

Theorem 1: A finite group G whose order |G| is divisible by a prime power pk has a subgroup of order pk.

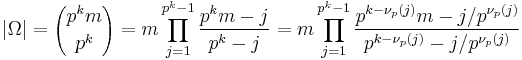

Proof: Let |G| = pkm = pk+ru such that p does not divide u, and let Ω denote the set of subsets of G of size pk. G acts on Ω by left multiplication. The orbits Gω = {gω | g ∈ G} of the ω ∈ Ω are the equivalence classes under the action of G.

For any ω ∈ Ω consider its stabilizer subgroup Gω. For any fixed element α ∈ ω the function [g ↦ gα] maps Gω to ω injectively: for any two g,h ∈ Gω we have that gα = hα implies g = h, because α ∈ ω ⊆ G means that one may cancel on the right. Therefore pk = |ω| ≥ |Gω|.

On the other hand

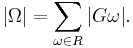

and no power of p remains in any of the factors inside the product on the right. Hence νp(|Ω|) = νp(m) = r. Let R ⊆ Ω be a complete representation of all the equivalence classes under the action of G. Then,

Thus, there exists an element ω ∈ R such that s := νp(|Gω|) ≤ νp(|Ω|) = r. Hence |Gω| = psv where p does not divide v. By the stabilizer-orbit-theorem we have |Gω| = |G| / |Gω| = pk+r-su / v. Therefore pk | |Gω|, so pk ≤ |Gω| and Gω is the desired subgroup.

Lemma: Let G be a finite p-group, let G act on a finite set Ω, and let Ω0 denote the set of points of Ω that are fixed under the action of G. Then |Ω| ≡ |Ω0| mod p.

Proof: Write Ω as a disjoint sum of its orbits under G. Any element x ∈ Ω not fixed by G will lie in an orbit of order |G|/|Gx| (where Gx denotes the stabilizer), which is a multiple of p by assumption. The result follows immediately.

Theorem 2: If H is a p-subgroup of G and P is a Sylow p-subgroup of G, then there exists an element g in G such that g−1Hg ≤ P. In particular, all Sylow p-subgroups of G are conjugate to each other (and therefore isomorphic), i.e. if H and K are Sylow p-subgroups of G, then there exists an element g in G with g−1Hg = K.

Proof: Let Ω be the set of left cosets of P in G and let H act on Ω by left multiplication. Applying the Lemma to H on Ω, we see that |Ω0| ≡ |Ω| = [G : P] mod p. Now p  [G : P] by definition so p

[G : P] by definition so p  |Ω0|, hence in particular |Ω0| ≠ 0 so there exists some gP ∈ Ω0. It follows that for some g ∈ G and ∀ h ∈ H we have hgP = gP so g−1hgP ⊆ P and therefore g−1Hg ≤ P. Now if H is a Sylow p-subgroup, |H| = |P| = |gPg−1| so that H = gPg−1 for some g ∈ G.

|Ω0|, hence in particular |Ω0| ≠ 0 so there exists some gP ∈ Ω0. It follows that for some g ∈ G and ∀ h ∈ H we have hgP = gP so g−1hgP ⊆ P and therefore g−1Hg ≤ P. Now if H is a Sylow p-subgroup, |H| = |P| = |gPg−1| so that H = gPg−1 for some g ∈ G.

Theorem 3: Let q denote the order of any Sylow p-subgroup of a finite group G. Then np | |G|/q and np ≡ 1 mod p.

Proof: By Theorem 2, np = [G : NG(P)], where P is any such subgroup, and NG(P) denotes the normalizer of P in G, so this number is a divisor of |G|/q. Let Ω be the set of all Sylow p-subgroups of G, and let P act on Ω by conjugation. Let Q ∈ Ω0 and observe that then Q = xQx−1 for all x ∈ P so that P ≤ NG(Q). By Theorem 2, P and Q are conjugate in NG(Q) in particular, and Q is normal in NG(Q), so then P = Q. It follows that Ω0 = {P} so that, by the Lemma, |Ω| ≡ |Ω0| = 1 mod p.

Algorithms

The problem of finding a Sylow subgroup of a given group is an important problem in computational group theory.

One proof of the existence of Sylow p-subgroups is constructive: if H is a p-subgroup of G and the index [G:H] is divisible by p, then the normalizer N = NG(H) of H in G is also such that [N:H] is divisible by p. In other words, a polycyclic generating system of a Sylow p-subgroup can be found by starting from any p-subgroup H (including the identity) and taking elements of p-power order contained in the normalizer of H but not in H itself. The algorithmic version of this (and many improvements) is described in textbook form in (Butler 1991, Chapter 16), including the algorithm described in (Cannon 1971). These versions are still used in the GAP computer algebra system.

In permutation groups, it has been proven in (Kantor 1985a, 1985b, 1990; Kantor & Taylor 1988) that a Sylow p-subgroup and its normalizer can be found in polynomial time of the input (the degree of the group times the number of generators). These algorithms are described in textbook form in (Seress 2003), and are now becoming practical as the constructive recognition of finite simple groups becomes a reality. In particular, versions of this algorithm are used in the Magma computer algebra system.

See also

Notes

References

- Sylow, L. (1872), "Théorèmes sur les groupes de substitutions" (in French), Math. Ann. 5 (4): 584–594, doi:10.1007/BF01442913, JFM 04.0056.02, http://resolver.sub.uni-goettingen.de/purl?GDZPPN002242052

Proofs

- Casadio, Giuseppina; Zappa, Guido (1990), "History of the Sylow theorem and its proofs" (in Italian), Boll. Storia Sci. Mat. 10 (1): 29–75, ISSN 0392-4432, MR1096350, Zbl 0721.01008

- Gow, Rod (1994), "Sylow's proof of Sylow's theorem", Irish Math. Soc. Bull. (33): 55–63, ISSN 0791-5578, MR1313412, Zbl 0829.01011

- Kammüller, Florian; Paulson, Lawrence C. (1999), "A formal proof of Sylow's theorem. An experiment in abstract algebra with Isabelle HOL", J. Automat. Reason. 23 (3): 235–264, doi:10.1023/A:1006269330992, ISSN 0168-7433, MR1721912, Zbl 0943.68149, http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/users/lcp/papers/Kammueller/sylow.pdf

- Meo, M. (2004), "The mathematical life of Cauchy's group theorem", Historia Math. 31 (2): 196–221, doi:10.1016/S0315-0860(03)00003-X, ISSN 0315-0860, MR2055642, Zbl 1065.01009

- Scharlau, Winfried (1988), "Die Entdeckung der Sylow-Sätze" (in German), Historia Math. 15 (1): 40–52, doi:10.1016/0315-0860(88)90048-1, ISSN 0315-0860, MR931678, Zbl 0637.01006

- Waterhouse, William C. (1980), "The early proofs of Sylow's theorem", Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 21 (3): 279–290, doi:10.1007/BF00327877, ISSN 0003-9519, MR575718, Zbl 0436.01006

- Wielandt, Helmut (1959), "Ein Beweis für die Existenz der Sylowgruppen" (in German), Arch. Math. 10 (1): 401–402, doi:10.1007/BF01240818, ISSN 0003-9268, MR0147529, Zbl 0092.02403

Algorithms

- Butler, G. (1991), Fundamental Algorithms for Permutation Groups, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 559, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, doi:10.1007/3-540-54955-2, ISBN 978-3-540-54955-0, MR1225579, Zbl 0785.20001

- Cannon, John J. (1971), "Computing local structure of large finite groups", Computers in Algebra and Number Theory (Proc. SIAM-AMS Sympos. Appl. Math., New York, 1970), SIAM-AMS Proc., 4, Providence, RI: AMS, pp. 161–176, ISSN 0160-7634, MR0367027, Zbl 0253.20027

- Kantor, William M. (1985a), "Polynomial-time algorithms for finding elements of prime order and Sylow subgroups", J. Algorithms 6 (4): 478–514, doi:10.1016/0196-6774(85)90029-X, ISSN 0196-6774, MR813589, Zbl 0604.20001

- Kantor, William M. (1985b), "Sylow's theorem in polynomial time", J. Comput. System Sci. 30 (3): 359–394, doi:10.1016/0022-0000(85)90052-2, ISSN 1090-2724, MR805654, Zbl 0573.20022

- Kantor, William M.; Taylor, Donald E. (1988), "Polynomial-time versions of Sylow's theorem", J. Algorithms 9 (1): 1–17, doi:10.1016/0196-6774(88)90002-8, ISSN 0196-6774, MR925595, Zbl 0642.20019

- Kantor, William M. (1990), "Finding Sylow normalizers in polynomial time", J. Algorithms 11 (4): 523–563, doi:10.1016/0196-6774(90)90009-4, ISSN 0196-6774, MR1079450, Zbl 0731.20005

- Seress, Ákos (2003), Permutation Group Algorithms, Cambridge Tracts in Mathematics, 152, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-66103-4, MR1970241, Zbl 1028.20002